An

experiment at the Barbican will look at how class-ridden the theatre

still is, but Richard Dryball set about his own investigationA

really good night in the theatre can be powerful. As the curtain comes

down it can make you ask fundamental questions about the world.

Sometimes it can even make you look in the mirror and say: ?What the

hell am I, where do I belong??

It?s unusual, however, to ask these big questions when you are

booking the tickets. But that?s exactly what happened to me when I rang

to buy a seat for Class Club, which opens at the Barbican

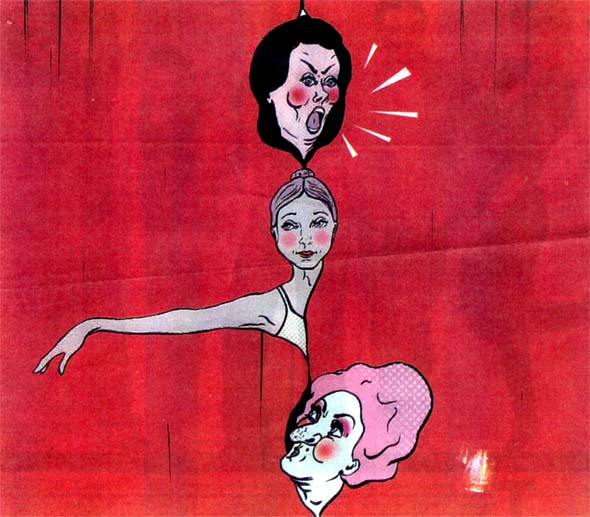

tonight. This is the latest dinner cabaret/theatre show from the Duckie

company. When you book, you have to specify what class of menu and

entertainment you would like, then pay either £14.99, £25 or £40,

according to which class you would like to be ? lower, middle or upper.

My

basic instinct, like many of us, is to settle on ?middle? and be done

with it. But that seems so bland. And, indeed, it turns out that Class Club?s

whole shtick is geared to the idea that middle-class means bland and

conservative. Those occupying the upper and lower tables, they tell me,

will be offered solid traditional fare with good service, and be

entertained with something specific, such as opera for the toffs and

bawdy comedy for the underclass. The middle will, they say, be ignored

or offered ?trendy world food? and a loose satire on contemporary

dance.

Now, OK, on the one hand this is just a clever way of cooking

up tabletheatre for the cognoscenti. But as I vacillated between the

options, and their accompanying menus, this made me wonder: to what

extent does going to the theatre cleave to such received notions of the

class system? And, hold up, what is the class system anyway?

The advertising industry tells us that we are now a classless

society, like America, where we are all either A, B or C, 1, 2 or 3.

Even if they are right, it still redefines ?society? as ?middle-class

society? and then subdivides us into lower, middle and upper anyway.

So I thought I?d test these assumptions with three trips to

three seasonal shows in locations where, rightly or wrongly,

expectations come with their own class filter. And this is the perfect

time of year to have a look. Apparently, each Brit goes to the theatre

about 1¼ times a year, mostly at Christmas. So I?ve opted to spend an

across-the-board tenner and go to see whether seasonal shows really do

still differ all that much according to the socioeconomic group that

you might traditionally expect.

I start with the ?working class? option: never mind your Mark

Ravenhills and your Ian McKellens, a ?traditional family panto? is

still seen as being as lowbrow as you can go without having the cast

writhe round a pole. In this case, I?ve opted for Dick Whittington

in Southend. Southend and I have some previous: it was on my last visit

here that I witnessed a panto nadir in the 1990s. I went to see Gary

Bushell as an execrable Robin Hood in a theatre that looked like a

bread factory.

On the train, post-pubescent boy gangs are flashing knives. As

I alight at Southend, random violence hangs in the air. I approach the

theatre and notice the cars parked outside ? the showboat end of the

4x4 genera. I go in with a heavy heart, but once inside, the place is

buzzing, the staff are fun, and most importantly this Whittington

is a belter. Not a Bushell in sight, just top pros giving us the full

panto treatment. Superb singing and dancing with pace and energy. Sarah

the Cook is a powerhouse, Cannon and Ball are fresh and funny and the

story is clearly told. It passes the true test: little boys, old ladies

and me, united in one-nation joy.

During the interval I fall in with Rod, a Southend

electrician, and his family. They are having a good time too. I ask

them if they?d ever been to the Royal Opera House. They say no. I ask

them if they would consider going to the Duckie show. They look at me

as if I am insane.

I head back to London. I?ve got an ?upper-class? experience tomorrow.

So to the ROH in Covent Garden, because the poshest man I?ve

ever met told me at a drinks do on a yacht that it is the only place he

will go for live entertainment. Never mind him, though, this is one of

the most accessible venues around. There?s something to please

everybody and every budget here. Students, children and the less

well-off are welcomed during the Travelex season, but you can see

world-class opera and ballet for £4 at any time. It?s a treat to come

here and enjoy the public space. The Floral Hall is breathtaking and

the outdoor terrace with a view over Covent Garden is magical. Rod and

his family would surely like it here too.

It?s the only theatre I?ve ever seen giving

away copies of the Financial Times.

The perceived image problem could be because it?s so

intimidating on arrival. Tonight the ticket hall is packed with the

City hedge-fund community. It?s the only theatre I?ve ever seen giving

away copies of the Financial Times. My £11 seat is high in

the amphitheatre, up with ?the paupers?, as Dame Edna would say, and

I?m surrounded by foreign backpackers. Below us are the well-shod.

Where are the ordinary Brits? What?s happened to the integration of

Shakespeare?s Globe when the ?penny stinkards? would see the same thing

as the wealthy?

Perhaps it?s because the Sleeping Beauty that we?re

here to see tells the story in a ludicrously old-fashioned way, with

stilted gestures and sets and costumes that haven?t changed much since

1946. The Duckie crowd would hate it ? far too little irony ? but they

won?t come because it?s obvious from the brochure what you will get.

It?s not for me either, but there?s no denying that it?s a show with a

very sure sense of itself.

Finally, then, to Kent. If Surrey is the beating heart of

middle England, then Tunbridge Wells is the administrative capital.

It?s not ?super-rich? so much as ?super-civilised?. This is where the Today

programme comes when it needs a nice vox pop on a ?middle-class

disaster?, such as inheritance tax. So I?m coming to the usually

reliable Trinity Arts Centre, to see an arty-looking Cinderella. In the café I see a bevy of women with their daughters, many of whom are wearing the blue dress from the classic Disney film.

Ten minutes into the show I feel uneasy. Is this Cinderella or

the local sixth-form doing their theatre A level practical exam? The

story is lost in earnestness. The young girls in the dresses who know

the tale best are most baffled. It?s a bit like popping your toddler in

front of CBeebies to find that Anthony Minghella has suddenly taken

over writing and directing The Tweenies.

It's as if Anthony Minghella had suddenly taken over directing The Tweenies

The seats start flipping up, and I join the polite exodus. In the café

I ask two women why they left with their four girls. They were

disappointed because they were hoping for a Cinderella that

their young children would recognise but wasn?t like a ?tacky

commercial panto?. They were hoping for ?something in the middle?. At

this point a rather snotty usher intervenes and, looking at me

directly, says: ?It gets better in the second half and it is actually

for young people.? At which I feel the classic middle-class emotion: embarrassment. So much so that I daren?t ask for my £10.95 back.

Experiment

completed, it?s time to reflect. The three venues are all doing good

business, trying to appease their different markets. But while I

thought they would conform roughly to their cartoonish class models, I

was astonished to see the sheer extent of the audience segregation.

There is a huge gulf in content between the upper and

lower-class shows, but Duckie has identified an important point: the

top and bottom are more satisfying because they share a shameless

clarity of intention. The middle way, where many of us belong, tries to

appeal widely and ?correctly?. The result is muddled and tame.

I just need to do one more unit of research. I?m now ready to book for Class Club.

But now I?ve got a tactic. I?ll pay the working-class money upfront,

then see if I can blag a free upgrade just before it starts. That?s not

too middle-class is it?